ikat dyeing, color, spatial illusion

February 25, 2012

NOTE: Skip if not interested in the procedural aspects of dyeing wool…though scroll down and see the embedded photographs of my work.

This entry somewhat overlaps an earlier post on ikat dyeing (aka space dyeing), but is more specific as to the preparation of the yarn and additions of color to the dye baths.

In an earlier entry on ikat dyeing (aka space dyeing), I showed photographs of pieces in which dots and dashes of color or natural white added visual texture. These white dots are the original color of the yarn before I dyed it. To have sections of the skein of wool yarn resist absorption of the dye, I tightly wrap and tie random (or regular) sections of the (washed/rinsed/preferably dried) skein with plastic tape made specifically for this use. Particularly if I want only white dots, I’ll wind/tie one wrap of bean string. I space the tied sections evenly or haphazardly depending on the effect I want. Then I immerse the skeins into the prepared, hot dye bath. This dye bath contains the proportions of the different dye solutions that make up the dye formula I’m using to get color X.

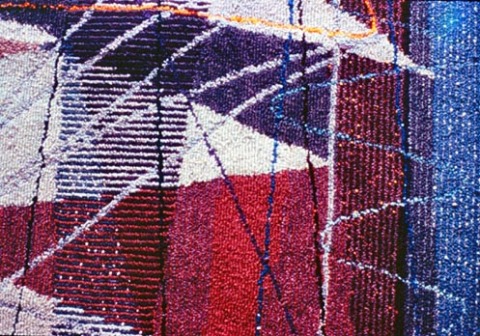

"African Folds," detail, © 1990

To get colored rather than white dots or dashes on the dyed yarn, the procedure is basically the same except that I have dye the same skein in different dye baths–an extremely labor intensive and time consuming process. Say I want a medium blue yarn with lighter blue dots/dashes. First I need to prepare the dye formula for the medium blue I want, but I will be using only 50% of this dye solution in the first round of dyeing to get the lighter blue that will become the colored dots/dashes. I go through a whole dye session to get this 50% lighter blue. When the dye bath is clear, the first round of dyeing is done. I remove the skeins from the hot pots and let them cool until I can handle them. I then tightly tie sections of the yarn with plastic tape or bean string. The length of the tape-wrapped sections depends on whether I want long or short dashes of light blue. (Tufting produces loops as the needle goes through the backing. The amount of yarn that goes into each loop determines where the dots/dashes will appear on the tufted surface.)

I prepare a new dye bath with the remaining 50% of the dye formula for my medium blue. The wrapped sections will not absorb this dye and will remain light blue. I go through the whole dyeing process again and this time the unwrapped yarn absorbs the other half of the original dye solution for medium blue. When the dye bath is clear (all dye has been absorbed), I’m done except for rinsing the yarn, removing all the plastic ties, admiring the dashes of light blue against the darker blue, and hanging the wet yarn to dry.

"Amazonas," detail, © 1986

Say I want a blue yarn whose formula is made up of 30% red, 10% black B, 10% yellow, and 50% of alizarine blue. I can get a blue yarn with red dots or yellow dots although these hues will not be a saturated red nor yellow, but rather a pink and light yellow (because of the amount of red and yellow the formula calls for). For red/pink dots/dashes I’d have to initially dye the skein only with the 30% red part of the formula for blue. I go through the whole dye process till the dye bath is clear, take out the red/pink yarn, let it cool and start tying sections with plastic tape. These wrapped sections will remain pink through subsequent dyeing sessions. For the next dyeing session, I prepare the dye bath with the remaining colors that make up the blue formula. I immerse the tied pink yarn into the dye bath and go through the whole process till the dye bath is clear. I end up with a blue yarn with pink dots or dashes. Had I wanted yellow dots/dashes, I’d have substituted the 10% yellow dye for red in the first dye session

If I wanted a blue yarn with yellow and white dots/dashes, I’d tie the “virgin” yarn skein with plastic wrap to cover sections that I want to keep white. I then dye the yarn in the 10% yellow solution; get my yellow yarn dyed, and tie sections with tape that will resist the rest of the blue dye formula which goes into the next dye pot. I add the yarn to get it dyed blue. When done, I unwrap all the plastic ties and end up with my blue yarn with white and yellow dots/dashes.

"Jigsaw Puzzle," detail, © 1987

I find that ikat dyeing for colored dots/dashes works well with medium to dark colors. With lighter colors, I go for white dots/dashes because usually the % amounts of colored dots/dashes in the dye formula for color X are so light as to be not worth the trouble.

"Square Rug," detail, © 1984

"Square Rug," detail, © 1984

"Square Rug," detail, © 1984

"Square Rug," detail, © 1984

I practically ran amok in “Square Rug” in the density and variety of color and visual texture imparted on the piece via ikat dyeing. I get my dots and dashes to work in two ways here, both having to do with the illusion of space. When I use ikat dyed yarn to fill an area or shape, that area of color is pushed into the background giving the impression of great depth, of infinite space. When I tuft a gestural line of ikated yarn and have it cut across shapes and ground, it pops to the foreground and pushes the shapes it traverses into an indefinite middle ground. Neat-o.

I don’t do ikat dyeing any more for large pieces…it’s just too laborious and my work has evolved beyond what its effects add to my artwork. Over the years I have simplified my colors and my compositions so much so that ikated yarns would detract from what I’m now after (in 2012). In fact, I’ve gone so far as to remove color from my work–other than black and white–as in the pieced white organdy constructions sewn onto black plexiglas and the black 3D rubber constructions I make. Also, my tufted wool compositions became simpler (which does not translate into less complex) as I pared down my palette to one or two colors. I made ikated yarns and mottled colors integral to my compositions at the time (mid-’80s/early ’90s). They contributed mightily to the chaos and gestural aspects of my work and in defining illusionist space. By now, as my work has evolved and in certain ways simplified, my visual vocabulary has changed. It’s a big relief not to have to spend hours in a high humidity and smelly dye lab (from the glacial acidic acid used in dyeing with acid dyes). I did enjoy dyeing at the time, but wouldn’t do it today. I just don’t have the stamina or strength to repeatedly lift water-sopped or hot dye-bath sopped, weighty, industrial skeins of wool yarn in and out of wash and rinse buckets or dye pots. When a commission comes along, I go into my notebooks with color yarn samples to find the colors I want and hire a professional dye facility that specializes in small batch dye projects.

more visual effects of ikat dyeing on tufted wool yarn

February 7, 2012

The white dots are the sections on the yarn that resisted dye absorption. These sections were wrapped with plastic tape at irregular intervals and in random lengths before the yarn was immersed in the dye bath.

The ikat-dyed yarn was tufted into the different shapes in alternate rows.

More visual texture and richness contributed by the ikat-dyed dots. The complex colors in this piece–the maroons and blues–are achieved through the use of toners which I referred to in an earlier post.

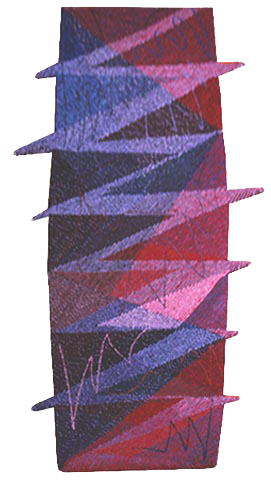

More complex colors, mottled yarn and ikat-dyed dots in an early piece, “Blackberry Winter #1” (1985). I made three “Blackberry Winter” pieces. Their main structural element is a large zigzag that cuts through the vertical middle of each piece, its zags (elbows) jutting out beyond the edge of the body of the piece giving it an irregular contour. I particularly liked breaking past the edges and made sure these extensions were integral to the composition–not just tacked on for effect.

Finding my way to art school

September 7, 2008

I did not come to making art from an art background. I got into art through the back door, so to speak, when I was in my thirties.

Growing up, I was exposed to every kind of stitchery having been born and brought up in Peru and elsewhere where such domestic needle skills are handed down from mother to daughter (are they still?) My Spanish grandmother was a stitching whiz. She could glance at a sweater and figure out how to knit it. Ditto with the crochet hook. She was also inventive: she knitted, crocheted, and embroidered on the fly–no notes, no pattern– everything skillfully made. Her house had a cuarto de costura–a sewing room–where her fabrics, yarns, and sewing basket were kept in a large armoire next to her sewing machine. I was very young then, yet remember whiling away afternoon hours there and having tea with my aunts or whoever had come by for a visit. I can bring back that special cozy feeling of contentment and warmth that room meant to me. Yet I myself wanted nada to do with sewing…I was a tomboy and couldn’t be less interested. Looking back: what a waste!

My early schooling did not include art classes—they weren’t offered. I take that back. In a junior high class in Bolivia I’d worked forever on a needlepoint project for the labores manuales class. It entailed filling in the background–in a mind-numbing beige yarn which came with the kit–of a pre-stitched figure of a bonnetted Victorian woman dressed in blue. I hated working on it. The teacher called me Penelope referring to the mythological character who every night for twenty years pulled out what she’d stitched during the day so as to thwart the advances of suitors as she delayed the completion of her project in anticipation of her husband’s return from the war.

Not having gone to school in the US (other than second grade), where by the time you are in high school you are thinking about college and about a career, I didn’t realize there were major choices to be made….that I could shape my life. I simply didn’t think in those terms for I’d never had to make such choices. I pretty much dutifully did as I was told. In hindsight, I’m aghast at my cluelessness. Such an ingenue! What was I thinking? Mostly, of getting educated, but not much beyond that.

Fast forward to undergraduate years. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I’d loved my freshman and sophomore years. I took courses from some inspired teachers: Prof. Frazer in Zoology, my first big lecture course; Prof. Alvin Whitley’s mesmerizing lectures on Romantic Poetry; Prof. Whelan’s (sp?) philosophy course in which I first encountered phenomenology. I didn’t consider taking art courses other than an art history class from an extraordinarily handsome and meticulously, starchedly dressed young professor who taught in the dark showing slides of Baroque painting toward which I’ve had a visceral revulsion to this day. Voluptuous female figures in unnatural, tippy-toed poses; picnic scenes of overdressed period characters; stage backdrop landscapes of peaks in distant misty blue. That negative art history experience did not encourage me to take more classes in art.

One summer session, I had a roommate from New York. She was taking a sculpture class and one day brought back to the dorm a maquette she was working on–a clay self-portrait. I was intrigued and incredulous: she was taking a college course that didn’t involve grinding reading and writing. She never had reading assignments nor a paper due. The world of studio art was unknown to me. Could students take such classes and make something out of a clump of clay for credit? The first and last time I’d done that was with Play Doh in nursery school. She seemed ordinary enough though more sophisticated and learned in music and art than I was. She didn’t look like what I’d imagined an artist should look like and dress like. She was my roommate and made art? Weren’t artists a breed apart?…geniuses?…in outre get-ups? How did she know she was an artist, or was it pure chutzpah on her part to aspire to be one? Where did she get ideas of what to make? Yet, here she was modeling a bust of herself–the problem of what to make solved. Perhaps making art was something one did during summer session. I wished I’d heard about it though with no experience in making art, I wouldn’t have dared to sign up.

The academic side of my junior and senior years at UW was a disappointment. My gringo father suggested I consider Hispanic Studies as a course of studies. He believed, with good intentions, that I ought to learn about my Spanish heritage. I dutifully declared my major. I took courses in Spanish and Latin American literature, civilization, and history by some pedantic scholars. The exception that stands out was a history course taught by Professor Philip Curtin whose interest was the African slave trade. He was thoroughly knowledgeable about his subject, passionate about ideas, and incisively clear thinking. He wholly engaged the students (most of whom were graduate students) for an intense, cerebral hour. Other than that course, I was not satisfied with my major, but I didn’t have the wit to switch.

Coda: Curious to know what had become of Prof. Curtin, I did a quick google search. It turns out he’s a highly respected historian who has caused seismic shifts in the focus of research on Africa. He’s written many influential and oft-quoted books. He shook things up with his sometimes controversial views as, for example, the historical relevance of oral tradition in Africa. Among his many honors, he’s a MacArthur Fellow! And he’s Professor Emeritus at Johns Hopkins University. Bravo Professor Curtin! I should have switched my major to African Studies!

In the Latin American context of classes I took (excluding Curtin’s), “civilization” began in 1492 with the arrival of the Spaniards. Whatever had occurred before was the dark ages. I got the distinct impression that what went before was not being studied nor worth studying since they were “primitive” cultures. Yet, actually, archaeologists, anthropologists, folklorists, and ethnobotanists were making discoveries along river valleys in the arid coast of Peru. They dug through middens counting unearthed beans and corn kernels and fish bones to determine food sources, harvests, droughts, and population sizes and movements; they unwrapped mummy bundles in grave sites finding clues to specialized classes of weavers which pointed to priestly hierarchies of rulers. Folklorists studied the oral traditions of ancient myths from pre-conquest times as written down by post-conquest scribes. There must have been university courses that covered these subjects, but I didn’t know about them. I would have loved to have studied them for I’d been brought up in the Andes in the midst of Quechua and Aymara Indians and felt an affinity for their cultures. I wish I’d learned to speak Quechua as a child, but now I see that such a notion then was unthinkable being of a class that denigrated the natives.

I also lacked the confidence to “follow my bliss” because I didn’t know what my bliss was. In retrospect, I was floundering. Through a process of elimination, I was beginning to find out what didn’t appeal to me. And by default and unawares–for I was not consciously seeking something to dedicate my life to—I was discovering what I had no passionate interest in nor natural ability for.

Fast forward to post-college years. I moved to Indiana with my professor husband (who I had met at UW) to a small college town where I dedicated myself to bringing up our two children. I hadn’t done much sewing other than mending torn jeans, replacing broken zippers and lost shirt buttons. Early in my marriage, my husband gave me the book Crafts Design by Moseley, Johnson and Koenig, which I still have. He realized I was searching for something I could apply myself to. My first effort at handicraft was to make a hooked throw rug (nesting?) using Aunt Lydia’s acrylic yarn from Woolworth’s. I made up the simple design–2 rows of a repeated orange escutchion on a solid green ground. B-o-r-ing. It reminded me of the tedious needlepoint effort in junior high. The rug’s colors were dull; the yarn had no spring to it for the pile matted down where stepped on.

It’s interesting that during those years my creative outlet found its way to textiles in one way or another. I dabbled in various sewing projects as a hobby learning techniques from library books. Before long I got my own books–mostly how-to books. An early purchase was Erica Wilson’s Embroidery Book which I still use for reference. I appliqued and embroidered baby quilts for the nursery wall based on Mother Goose rhymes. I stitched dolls and felt Christmas tree ornaments from patterns in magazines like Woman’s Day that I’d pick up at the supermarket checkout counter. A couple of useful books were Jean Laury’s on applique followed by Beth and Jeff Gutcheon’s inspiring book on making quilts (both of these I loaned to someone long ago and never got back–grrrr). The Gutcheon book drew me in the direction of quilts. I pieced traditional quilt blocks which eventually led to my developing original designs. For awhile I was enamored of trapunto and made several white pillows and wall hangings.

Needing pin money to help finance my needlework–but mostly to make space for new projects–one October I rented space for a booth at the week-long Covered Bridge Festival in nearby Mansfield. It was a particularly cold and wet week, but I sold some quilts which made the effort worthwhile.

Probably my most ambitious project was learning how to silk screen on fabric (can’t recall which book taught me the basics). I designed a series of animals that I silk-screened on a one-yard square of muslin. The animals were in pattern pieces, to be cut out, sewn together and stuffed with polyfill. It had been exacting work to figure out the patterns so as to get a fully realized 3-D boa constrictor or whale or rhinoceros or elephant when the corresponding pieces were sewn together. In truth, I preferred to look at the fragmented parts inked on the muslin square pinned to a wall more than the finished stuffed animal. Something about the 2-D sharp and abstract silhouettes of the patterns appealed to me. They are as close to being art objects as anything I’d made till then. I could just as easily have silk-screened drawings on paper, but fabric was the draw and fragmented patterns the means.

In 1977, I participated in a national quilt contest–the “Flower Garden Quilt Contest”–sponsored by the Indianapolis Star newspaper. It was my first entry into a juried show. The contestants were each to produce a quilt based on a set of 24 flower designs by Ruby McKim. You could stitch them any way you liked, but the sponsors wanted contemporary interpretations–not what your grandmother would have made. I decided on bold, solid colors using a reverse applique technique to render stylized versions of the traditional McKim designs. I was influenced by “The Rockefeller Quilt” designed by Dorothy Weatherford, designer for the Mountain Artisans Cooperative of West Virginia. (That quilt was a gift from the quilters to Sharon Percy Rockefeller for her support in their efforts to establish and maintain their cooperative.) The Flower Garden contest drew many beautiful and inventive entries. In the end, I won first place with mine, which disgruntled many. Yet one viewer at the show declared it was “the only contemporary quilt” there. It was a welcome compliment amidst the dissenting noise. Coda: The quilt was purchased by Sharon Rockefeller.

By now I’d grown restless. Women were seeking fulfillment outside the home. Feminism was in the air and I was receptive to its message. Domesticity and female handiwork were out; careerism and using one’s brain were in. Stirrings of dissatisfaction percolated–of something missing or my missing out. Taking care of the children was becoming less demanding now that they were in school. I had time on my hands. I knew I could be accomplished at something…but what? I didn’t want to pursue stitchery because it couldn’t shake the perception of its being a hobby. In addition, it had all that baggage of female domesticity–the taint of brainless women’s work. Getting a brainy advanced degree seemed doable and the way to go with Indiana University (IU) being fairly close (Bloomington is an hour’s drive from our house). And my husband would be taking a sabbatical year off from teaching so he could cover the home front while I was away during the day. I discovered that IU offered courses in authocthonous cultures…Andean even. I got curious…

Looking through the IU graduate courses offerings, I find that so-called “primitive” cultures are a legitimate field of study. I was elated. I signed up for courses toward an M.A. degree in Latin American Studies intending to study pre-Columbian subjects. What I “would do with it” I wasn’t sure…something would develop. My husband was agreeable to this venture so off I went, commuting daily to Bloomington. I studied hard for I’m a grind. Andean textiles caught my eye–their colorful and orderly abstraction and stylization. At the suggestion of my advisor, Professor Roy Sieber, I signed up for a beginning weaving course with Budd Stalnaker in the Fine Arts School to learn the nuts and bolts of how textiles are made. Unbeknownst to me at the time, this course would change my life.

Budd’s interests lay beyond the mechanics of cloth-making (though he was a bear about teaching the techniques and the students’ mastery of the loom and dyeing). His was an art studio class and Aesthetics was his numero uno concern. He knew more about color than most artists and had an incredibly discerning eye. Teaching us how to see by way of leading questions was a central part of class critiques. I soon realized that more was expected of me than producing even selvages.

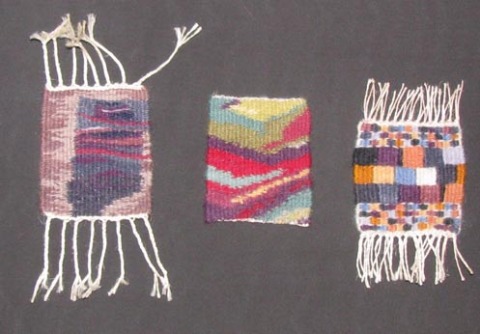

These are samples of early tapestry class assignments. They’re 3″ x 3″ studies in 2-ply wool yarn on a linen warp, my first serious creative efforts in fiber. Each was my solution to an assigned problem. Baby steps.

I’d never thought of weaving as brain work, yet all the assignments in “Beginning Woven and Constructed” involved problem-solving of a kind I found to be challenging and satisfying work. I’d never thought of myself as an artist; making art was what artists did. Yet in the Fine Arts building I was among people who took making art seriously and discussed aesthetics on a higher plane than as mere technique. It was a revelation to me that others responded as I did to, say, a red mark on a black ground. They didn’t just respond to such an aesthetic experience, but dedicated their lives to making such marks. I was home.

I decided to apply to the MFA program in fiber. I recall the interview I had with Budd in which he seemed concerned about my being able to switch from a verbal to a visual vocabulary. For whatever reasons, he accepted me into the graduate program. I now think that I was always a visual person but had been living in a verbal universe. I’d been a fish out of water. Now I was in my element and Budd was offering me a chance to swim.